Are restraint of trade clauses worth the paper they are written on? Are restraints of trade clauses even enforceable?

These two questions are perennial concerns for employment lawyers, and they’ve gained renewed attention in the wake of the recent Federal Election. Historically, restraint of trade clauses were presumed void at common law unless they protected a legitimate business interest and were reasonable in scope. However, to say that such clauses are inherently ineffective in today’s legal environment is far from the truth.

What is a Restraint of Trade Clause?

The term “restraint of trade” is commonly used to refer to clauses in employment contracts that are designed to protect a business’s legitimate interests. These clauses typically operate to prevent former employees from engaging with direct competitors or from soliciting their old employer’s clients, and from using confidential information obtained during their employment.

It is standard practice for employers to require employees to make express contractual promises not to compete with the business or misuse confidential information after the end of their employment. This is usually achieved through well-drafted restraint of trade and confidentiality provisions included in employment agreements.

The enforceability of a restraint of trade clause depends on its reasonableness, both in scope and in protecting a legitimate interest of the employer. A restraint that is too broad or appears to serve no legitimate business purpose is likely to be deemed void.

When assessing whether a restraint is enforceable, courts will weigh the competing interests involved, including:

- The employee’s right to earn a living using their legitimately acquired skills, experience, and knowledge;

- The public interest in promoting competition and ensuring access to skilled labour; and

- The employer’s interest in protecting confidential information, customer and supplier relationships, and other commercial connections developed through significant investment of time, money, and resources.

Are Restraints Enforceable?

The short answer is yes, but it depends. It is becoming increasingly common for the Courts to hold employees to their contractual obligations and promises, enforcing restraint of trade clauses if reasonable.

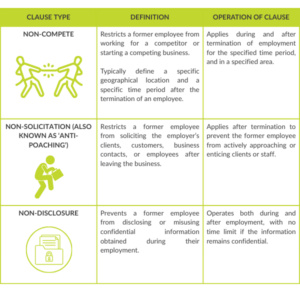

Three main types of restraint of trade clauses exist, being:

- Non-compete clauses;

- Non-solicitation clauses; and

- Non-disclosure clauses.

Courts take a cautious approach to enforcing post-employment restraints, taking several factors into account to determine if a restraint is enforceable.

The courts will first consider what interest the employer seeking to protect and whether it is a legitimate protectable interest. It is not as simple as an employer merely seeking to prevent an ex-employee from competing. In fact, clauses that seek to simply prevent competition will not be enforceable. Employers must rather establish that if the employee is able to compete, the company will suffer real harm to a recognised legally protectable interest. The protectable interests that are currently recognised include:

- Client and employee connections;

- Confidential information; and

- Springboard conduct.

If the court is satisfied that a protectable interest exists, it will then assess whether the restraint clause seeking enforcement is reasonable. In doing so, the court will consider factors such as the duration of the restraint and its geographical scope. If a restraint is found to be unreasonable, the court may strike it out in its entirety.

Courts will not rewrite an unreasonable clause to make it enforceable. However, where a “cascading” restraint clause is used, setting out multiple time periods or geographic areas in the alternative, the court may enforce the combination it considers to be reasonable. These “cascading” clauses are often used to allow courts to read down what would otherwise be the unreasonable operation of the restraint.

It is also important to note that in New South Wales, the Restraints of Trade Act 1976 (NSW) allows the courts greater flexibility. Under this legislation, a court is not strictly bound by the terms of the clause as drafted. Instead, the Court is given the discretion to read down the restraint to what it considers reasonable in the circumstances.

In the recent case of Jackson Power Real Estate Pty Ltd v Jones [2024] NSWSC 1665, the court clarified that confidentiality provisions within a contract cannot be expanded to create a de facto restraint of trade. This case emphasises that if employers seek to prevent competition from former employees, they must include express post-employment restraints within their contract.

Ultimately, while restraint of trade clauses can be enforceable, their success depends heavily on careful drafting. Employers should ensure restraints are appropriately tailored to the employee’s role, level of access to confidential or commercially sensitive information, and the specific risks posed upon their departure. A well-drafted clause, grounded in legitimate business interests, is far more likely to withstand judicial scrutiny.

Federal Election Update

Restraint of trade clauses, particularly non-compete provisions became a key policy focus during the recent Federal election. As part of its 2025–26 Federal Budget commitments, the Albanese Government announced plans to reform the use of non-compete clauses in Australia, with the stated aim of promoting productivity and increasing wages.

The Government’s initial proposal involves banning non-compete clauses for workers earning below the high-income threshold under the Fair Work Act 2009 (Cth). The high-income threshold is currently set at approximately $175,000 per annum. If implemented, this change is expected to affect around three million workers nationwide.

In its original media release, the Government indicated that following consultation and the passage of legislation, the reforms would become enforceable by 2027. However, since the election, there have been no further official updates or detailed announcements outlining the next steps or legislative timeline.

Restraint of Trade v Non-Solicit Clauses

Restraint of trade is a broad term used to refer to a range of clauses that seek to protect the employer’s interests. Restraint of trade clauses, include restraint on competition (preventing the employee from working for a competitor), and non-solicitation clauses that prevent the employee from soliciting clients, customers and employees.

How have the courts dealt with restraint clauses?

In AEI Insurance Group Pty Ltd v Martin (No 4) [2024] FCA 1110, the applicant sought to enforce employment restraints contained in the applicant’s employment contract. The clauses imposed restraints on the use of confidential information, engagement in competition and solicitation of clients for 12 months after the employment terminated. AEI began proceedings by seeking an interlocutory injunction to restrain Mr Martin from soliciting AEI clients, which was granted.

Mr Martin resigned and obtained employment at MA Brokers, a direct competitor with AEI Insurance. Mr Martin was provided with a mobile phone as part of his duties at AEI, and it was alleged that Mr Martin contacted AEI clients before his resignation, indicating that he was leaving and then providing his new contact number. Additionally, AEI alleged that a total of 51 of their clients had moved to MA Brokers after Mr Martin had left AEI.

In the final hearing, Justice Thawley ordered Mr Martin to pay $500,000 in damages for breaching a non-solicitation clause. The decision discussed AE’s protected interests, noting that in the context of insurance, brokers’ policies run for a period of 12-months and therefore the period dictated in the restraint was reasonable.

Similarly, in the case of Australian Timber Supplies Pty Ltd v Welsh [2021] QSC 266, an interlocutory injunction was sought to restrain Mr Welsh from operating a new business in direct competition with Australian Timber Supplies Pty Ltd (ATS), being his former employer. Mr Welsh established a new company before his resignation and commenced trading after leaving ATS in competition with them. The Court held that Mr Welsh’s actions in establishing the new business, breached the exclusivity clauses contained within his employment contracts. Mr Welsh’s employment contract required him to obtain written consent before conducting or undertaking work for another corporate entity or engaging with a competing business for 12 months post-termination. The court held that Mr Welsh had breached his restraints, noting that he had begun working for a direct competitor. The Court granted an interlocutory injunction in favour of ATS, restricting Mr Welsh from conducting his business.

In Liberty Financial Pty Ltd v Jugovic [2021] FCA 607 an interlocutory injunction was sought to restrain Mr Jugovic from taking a new position with a competing business. Mr Jugovic was employed with Liberty Financial Pty Ltd (Liberty Financial) for close to 20 years, providing financial loans to various markets. Mr Jugovic had clear restraints within his employment contract restricting him from providing “similar services” to other entities for a period of 12 months post termination. After resigning from Liberty, Mr Jugovic obtained employment with ORDE Financial Pty Ltd (ORDE).

Liberty Financial argued that due to Mr Jugovic’s role with his new employer being “executive director, debt capital markets”, he would provide similar services as those provided at Liberty. It was held that ORDE operated a similar business to Liberty Financial, having a similar customer base, network and product offerings. Additionally, due to Mr Jugovic’s senior position at Liberty Financial, he had access to Liberty Financials key information. The Court granted Liberty Financial the interlocutory injunction, restraining Mr Jugovic from commencing employment with ORDE.

In Label Manufacturers Australia Pty Ltd v Chatzopoulos [2022] NSWSC 1059, the Court discussed the reasonableness of a restraint clause drafted with a large scope and a long time period. Mr Chatzopoulos was employed at Label Manufacturers Australia Pty Ltd (‘LMA’) as the CEO from 2018, previously being employed in another company within the corporate group. Mr Chatzopoulos was made redundant and then placed on gardening leave for a period of 6 months, after which time he began new employment with a direct competitor of LMA.

LMA sought an injunction to enforce the covenants contained within Mr Chatzopoulos’s employment contract, specifically his restraints of trade to prevent him from soliciting clients and employees and being involved in any business which competed with LMA. The most exhaustive restraint operated for two years post-termination and applied in North America, Europe and most of the Asia-Pacific region.

The Courts noted that the restraints must be assessed with regard to the circumstances that existed at the time of the drafting. The Court raised several issues with the restraints, such as their lack of specificity, wide scope and blanket bans in circumstances where confidential know-how was not in issue. Additionally, the competition restraint was construed to apply to Mr Chatzopoulos’ potential employment in a competing business in any capacity. Therefore, the constraint was drafted to restrain Mr Chatzopoulos from engaging in any role within a competitor’s business, even if his role presented no competitive threat.

Mr Chatzopoulos held the role of CEO at LMA but was not solely responsible for managing customer relationships in the way a sales manager might be. The Court found that the seven-month period between his termination and the hearing was sufficient for his successor to establish client connections. Furthermore, the confidential information he possessed was not significant enough to justify the broad and extended restraints imposed.

It is clear that the courts are willing to enforce restraint of trade clauses that are clear, unambiguous and go no further than to protect an employer’s legitimate business interests. In this regard, employees should be very careful to ensure they comply with their obligations, as failure to do so can be extremely costly.

What Should Employers Do?

Prudent employers can take the following steps to effectively protect their business goodwill:

- Ensure employment agreements are current and include well-drafted, reasonable confidentiality and restraint of trade clauses.

- Tailor restraint clauses to each role, ensuring they protect the employer’s legitimate business interests and reflect the individual employee’s access to sensitive information, clients, or strategic knowledge.

- Conduct exit interviews with departing employees to reinforce their ongoing post-employment obligations.

- Follow up in writing with high-risk departing employees to remind them of their specific post-employment restrictions.

- Where there is a concern that a former employee may be breaching their obligations, take prompt action by placing them on notice and confirming that any breach will be treated seriously and may result in enforcement action.

What Should Employees Do?

Employees should carefully review their contracts and consider:

- Whether a restraint provision exists in the contract and the extent of its operation;

- If any restraint is overly burdensome or oppressive and seek amendment before executing the contract;

- Upon transition from a business to a competing entity, whether they are in possession of confidential information, ‘trade secrets’ or any other information that can be considered to be a legitimate protectable business interest of their former employer/principal; and

- Treat restraints of trade clauses seriously and inform prospective new employers or principals of any post-employment or engagement obligations they owe.

If you wish to discuss any aspect of this article or require specialist advice or assistance in relation to an employment law issue, please do not hesitate to contact us.

This alert is not intended to constitute, and should not be treated as, legal advice.

This article is for general information purposes only and does not constitute legal or professional advice. It should not be used as a substitute for legal advice relating to your particular circumstances. Please also note that the law may have changed since the date of this article.